library(lme4)Loading required package: Matrix?sleepstudy

s <- sleepstudy

Final Project Due.

Next Week : Virtual RRR Time (on Zoom) 11-????

Outstanding Grades : prof will do ASAP

Brain Exam

Discussion Posts

Discussion Presentations

Attendance / Check-Ins.

A classic teaching dataset from lmer. Hooray!

A Question : Is there a relationship between number of days of sleep deprivation and reaction time?

How might we graph this in ggplot?

What model would we define?

Reaction is the DV

I’m adding Days as a Fixed IV (so I’ll get the average effect of # of days of sleep deprivation on reaction time)

I’m also adding a random intercept : (1 | Subject) that will estimate how much the intercept (the 1 term) of individual raction times (the level 2 variable) varies by Subject (the level 1 grouping variable).

Linear mixed model fit by REML ['lmerMod']

Formula: Reaction ~ Days + (1 | Subject)

Data: sleepstudy

REML criterion at convergence: 1786.5

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.2257 -0.5529 0.0109 0.5188 4.2506

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

Subject (Intercept) 1378.2 37.12

Residual 960.5 30.99

Number of obs: 180, groups: Subject, 18

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error t value

(Intercept) 251.4051 9.7467 25.79

Days 10.4673 0.8042 13.02

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

Days -0.371How do we interpret the results of this model?

Fixed Effects : these deal with the “average” effects - ignoring all those important individual differences (which are accounted for in the random effects.)

Intercept = 251.41 = the average person’s reaction time at 0 days of sleep deprivation is 251.4 milliseconds.

Days = 10.47 = for every day of sleep deprivation, the average person’s reaction time increases by 10.47 MS; the standard error is an estimate of how much variation we’d expect in this average slope due

Random Effects : these describe those individual differences in people’s starting responses to the DV (random intercepts) and individual differences in the relationship between the IV and the DV (random slopes).

Subject (Intercept) = 37.12

Residual = 30.99

What model would we define?

Linear mixed model fit by REML ['lmerMod']

Formula: Reaction ~ Days + (Days | Subject)

Data: sleepstudy

REML criterion at convergence: 1743.628

Random effects:

Groups Name Std.Dev. Corr

Subject (Intercept) 24.741

Days 5.922 0.07

Residual 25.592

Number of obs: 180, groups: Subject, 18

Fixed Effects:

(Intercept) Days

251.41 10.47 How do we interpret the results of this model?

ICE BREAKER : what’s your favorite place in the bay area to see nature?

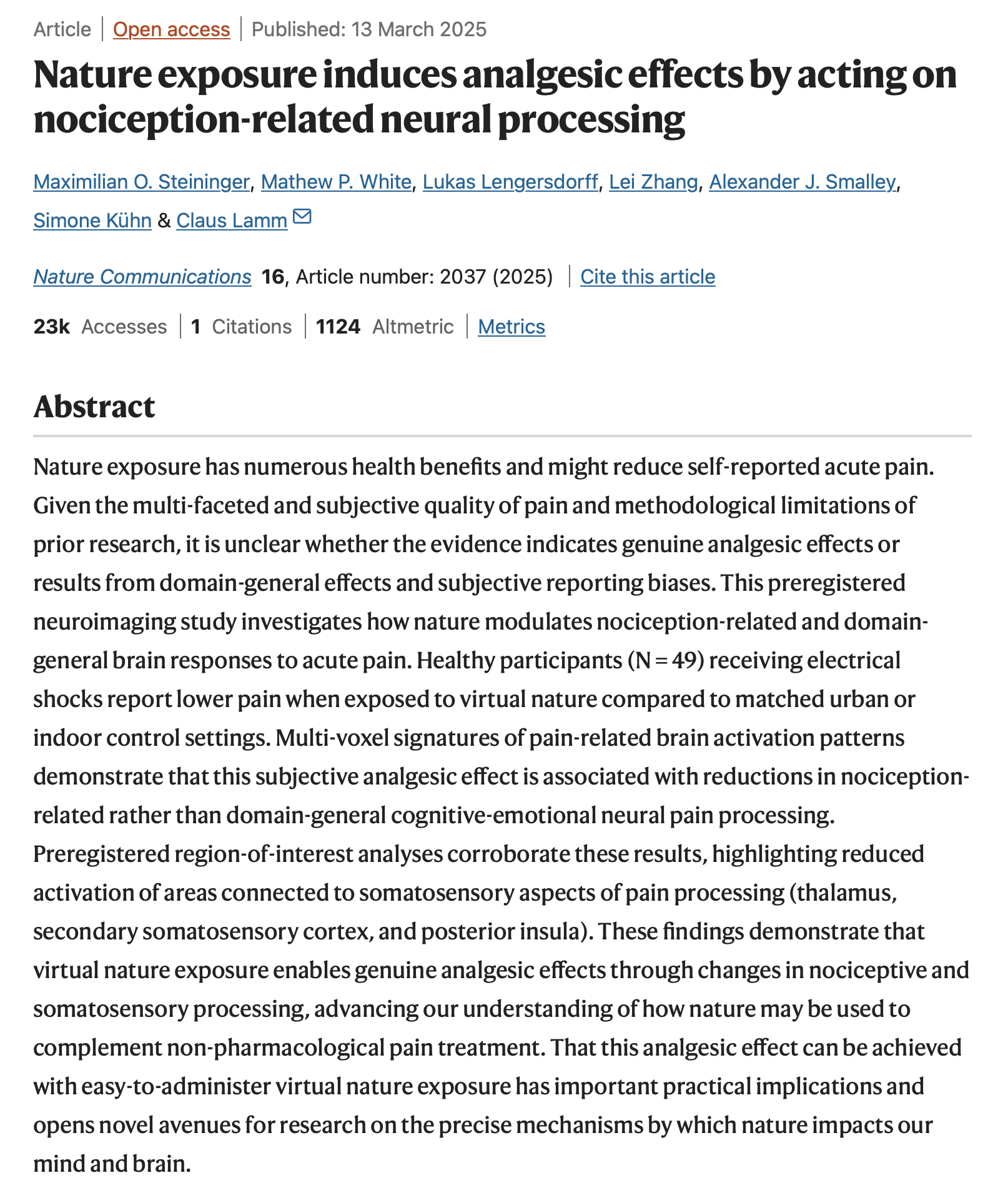

THE STUDY : participants were shocked while looking at images (virtual nature, urban, or indoor) while getting their brains scanned. participants rated the subjective unpleasantness of each trial.

THE TABLE :

What is going on with this models?

What seems important?

What seems irrelevant?

What questions do you have?

| Abstract [full article] | Linear Model Table [link to SI materials] |

|---|---|

|

|

Find a Buddy.

Walk them through your study!

What is your question (and why should we care)?

How did you measure / manipulate these variables?

Walk them through your graph / results!

Some volunteers to share with the class? Low-stakes practice for more stressful situations where you will be more prepared :)

Common Statistical Mistakes. Any you are doing? Questions?? Feeling the pressure???

Absence of an adequate control condition/group

Interpreting comparisons between two effects without directly comparing them

Spurious correlations

Inflating the units of analysis

Correlation and causation

Use of small samples

Circular analysis

Flexibility of analysis

Failing to correct for multiple comparisons

Over-interpreting non-significant results

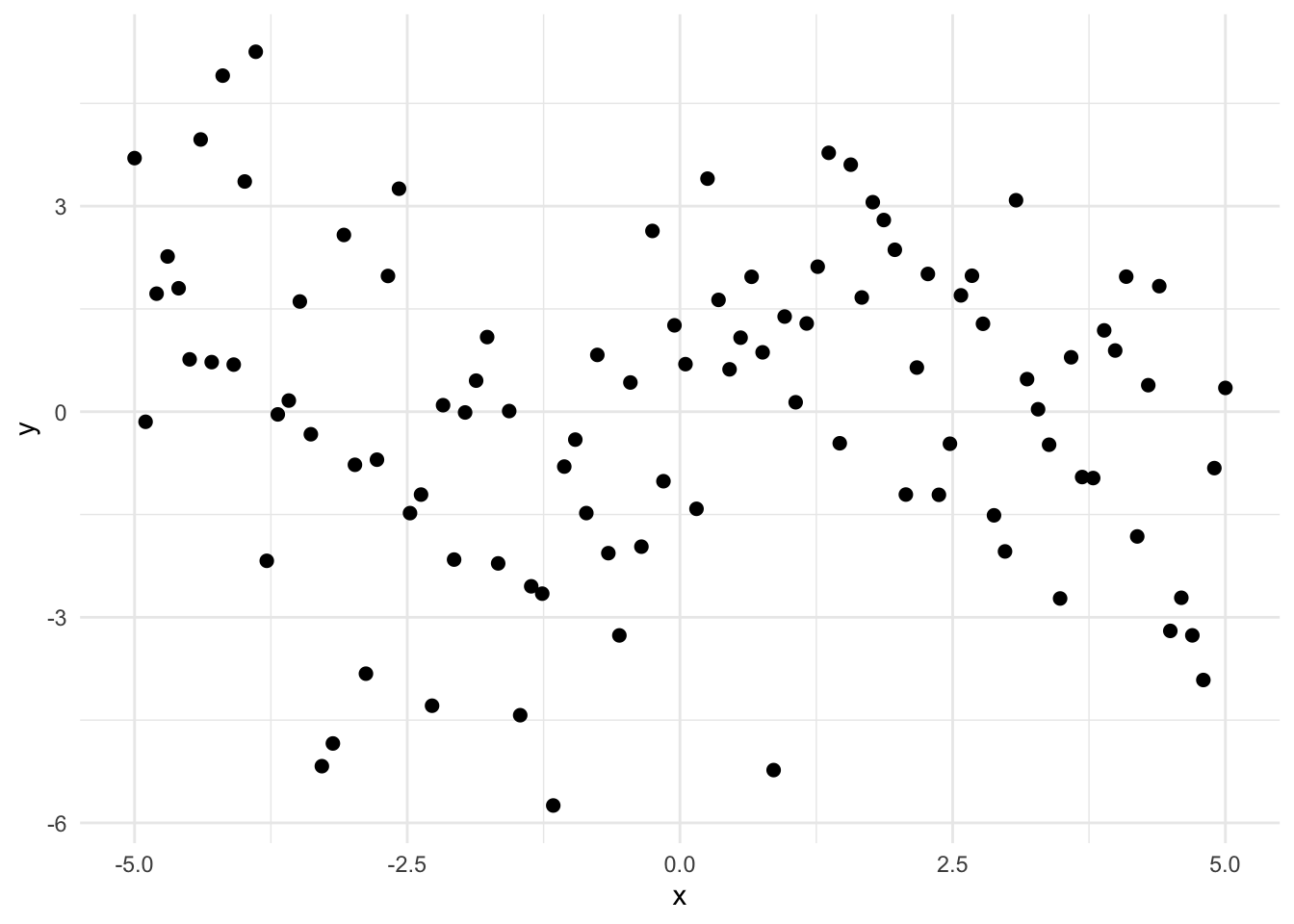

When your model is too complex, each variable in the model (parameter) increases the model complexity.

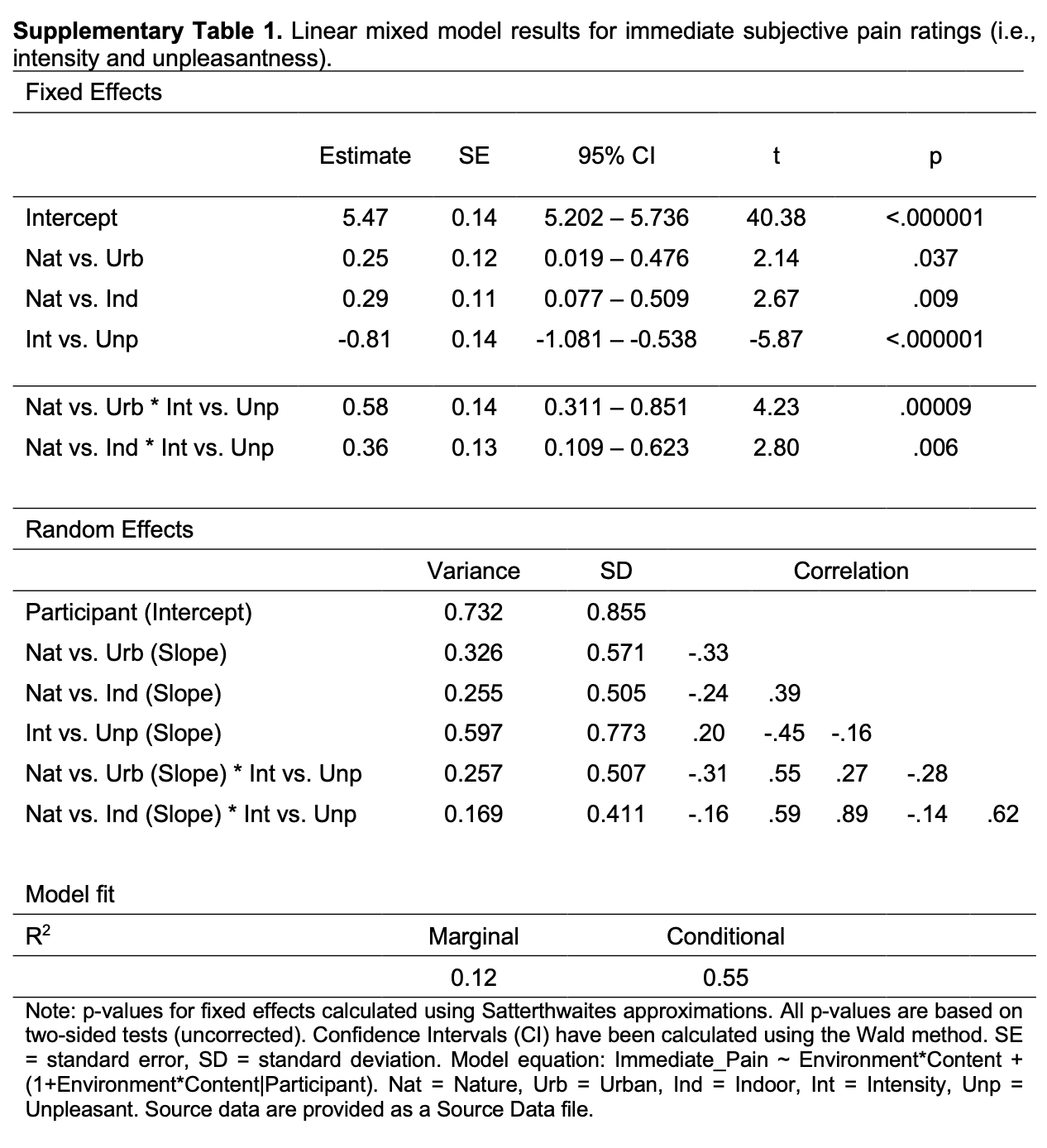

library(ggplot2)

# Fakin' some data.

set.seed(42)

n <- 100

x <- seq(-5, 5, length.out = n)

y <- sin(x) + rnorm(n, sd = 2)

d <- data.frame(x, y)

# Graphin the fake data.

ggplot(d, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point(size = 2) +

# stat_smooth(method = "lm", formula = y ~ poly(x, 25), se = FALSE, color = "red", size = 2) +

# labs(title = "Overfit Model (25-Degree Polynomial IV") +

theme_minimal()

KEY IDEA : complex models that perfectly fit the data are problematic

We don’t expect over-fit models to generalize to other samples. [Image source]

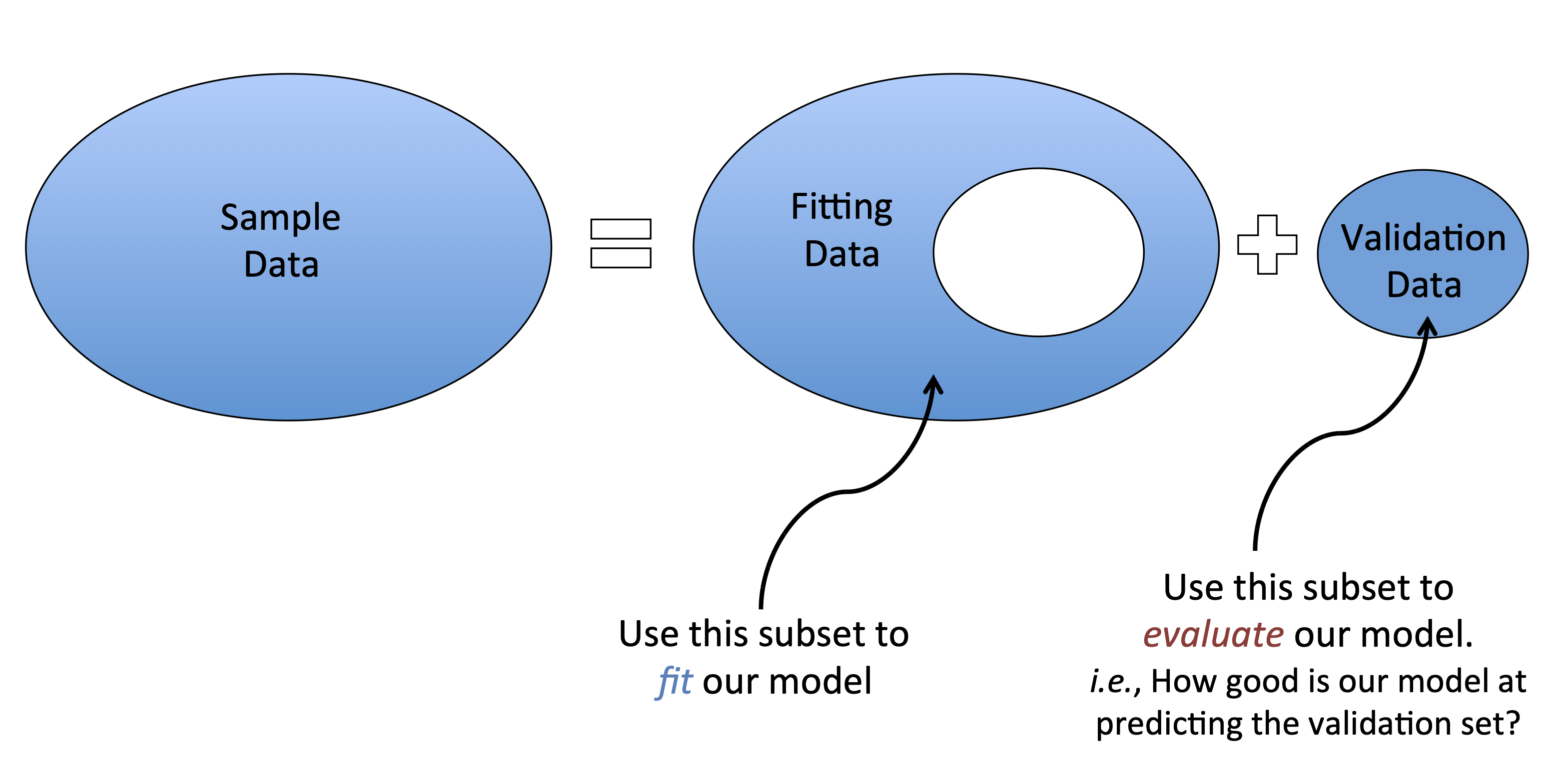

Cross Validation. To ensure your model generalizes to other samples, you can a) replicate, or b) cross-validate your data. Cross validation involves dividing your sample into sub-samples; define a model on one sample, then test the model in the other(s).

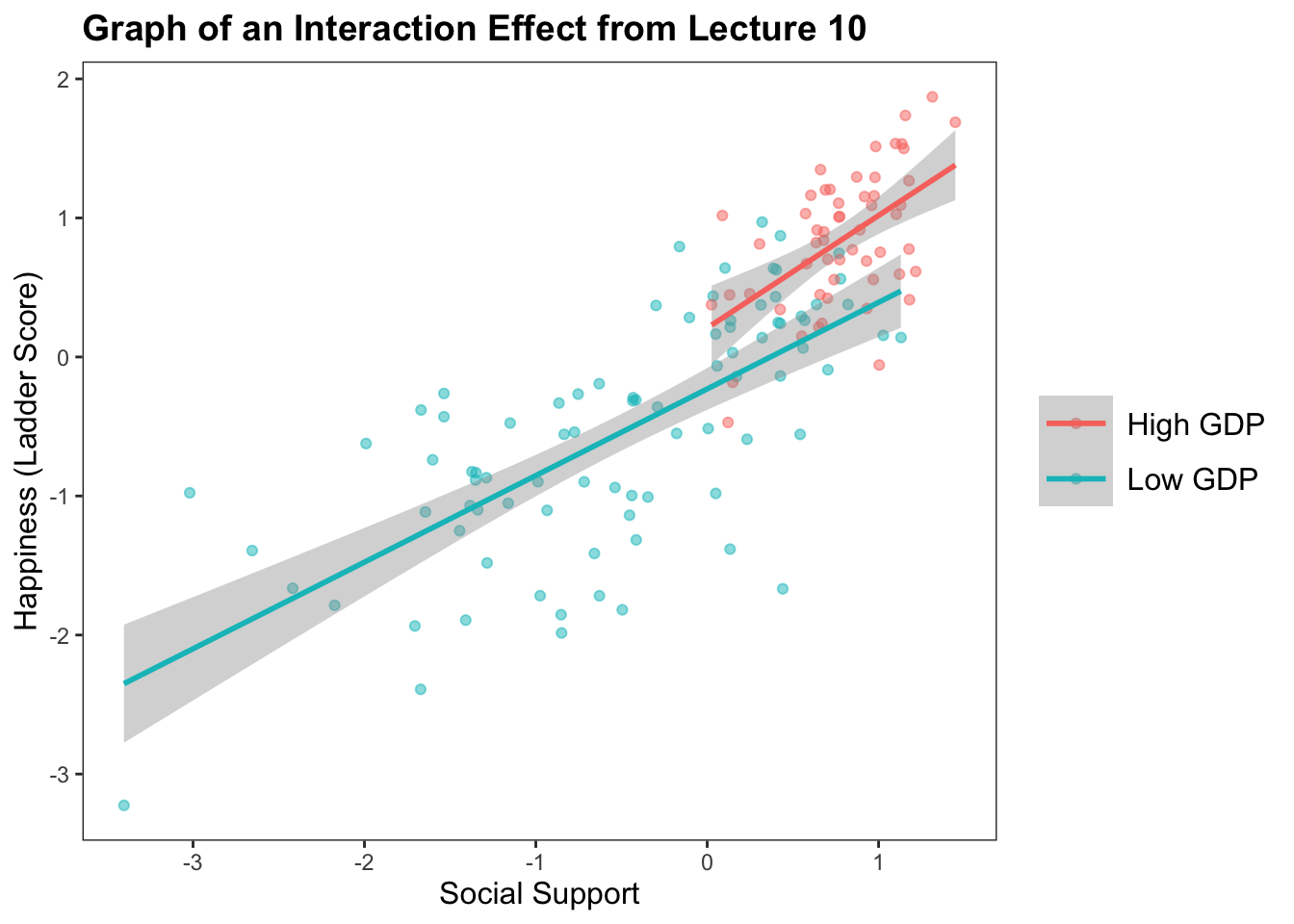

The Graph : The Relationship Between Social Support and Happiness Depends on GDP

h <- read.csv("~/Dropbox/!GRADSTATS/Datasets/World Happiness Report - 2024/World-happiness-report-2024.csv", stringsAsFactors = T)

library(ggplot2)

library(jtools)

## Some data cleaning.

h$GDPcat <- ifelse(scale(h$Log.GDP.per.capita) > sd(h$Log.GDP.per.capita, na.rm = T), "High GDP", "Low GDP")

h$GDPcat <- as.factor(h$GDPcat)

# plot(h$GDPcat) # making sure this re-leveling worked.

ggplot(data = subset(h, !is.na(h$GDPcat)), aes(y = scale(Ladder.score), x = scale(Social.support), color = GDPcat)) +

geom_point(alpha = .5, position = "jitter") +

geom_smooth(method = "lm") + labs(title = "Graph of an Interaction Effect from Lecture 10") + xlab("Social Support") + ylab("Happiness (Ladder Score)") +

theme_apa()`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Table : Linear Models for the Interaction Effect from Lecture 10

mod1 <- lm(scale(Ladder.score) ~ scale(Log.GDP.per.capita), data = h)

mod2 <- lm(scale(Ladder.score) ~ scale(Social.support), data = h)

mod3 <- lm(scale(Ladder.score) ~ scale(Log.GDP.per.capita) + scale(Social.support), data = h)

mod4 <- lm(scale(Ladder.score) ~ scale(Social.support) * scale(Log.GDP.per.capita), data = h)

export_summs(mod1, mod2, mod3, mod4)| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.09 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.06) | |

| scale(Log.GDP.per.capita) | 0.78 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.34 *** | |

| (0.05) | (0.07) | (0.07) | ||

| scale(Social.support) | 0.82 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.64 *** | |

| (0.05) | (0.07) | (0.07) | ||

| scale(Social.support):scale(Log.GDP.per.capita) | 0.13 * | |||

| (0.06) | ||||

| N | 140 | 140 | 140 | 140 |

| R2 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05. | ||||

Here’s the most simple example of cross-validation (“train-test split”; “holdout cross validation”)

[1] 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0

[38] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0

[75] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

[112] 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0set.seed(424242)

random.selection <- sample(0:1, nrow(h), replace = T, prob = c(.7, .3))

htrain <- h[random.selection == 0,]

htest <- h[random.selection == 1,]

## Model in training Data

train.mod <- lm(Ladder.score ~ Social.support * Log.GDP.per.capita, data = htrain)

summary(train.mod)

Call:

lm(formula = Ladder.score ~ Social.support * Log.GDP.per.capita,

data = htrain)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.6407 -0.3823 0.0727 0.3667 1.2845

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3.3152 0.8238 4.024 0.000133 ***

Social.support 0.7625 0.7030 1.085 0.281444

Log.GDP.per.capita -0.3721 0.8248 -0.451 0.653165

Social.support:Log.GDP.per.capita 1.1410 0.6266 1.821 0.072497 .

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.6336 on 77 degrees of freedom

(2 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.7538, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7442

F-statistic: 78.57 on 3 and 77 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16 1 2 4 6 7 8 9 10

7.135230 7.073353 6.977285 6.893786 7.124321 6.861858 6.871832 6.829994

12 13 17 18 19 20 21 22

6.226749 6.540176 6.959481 6.877903 6.696600 6.404965 6.856755 6.098574

24 29 31 34 35 37 38 39

6.646297 5.768824 6.485067 6.880177 6.558980 6.244588 6.282021 6.446558

41 42 44 46 51 53 54 55

6.385499 5.418369 5.821278 6.757584 6.442304 5.341571 5.710209 6.412559

58 60 61 63 65 67 68 70

6.070923 5.819241 4.986850 6.600110 5.978203 5.782169 5.550716 6.199191

74 75 79 84 85 86 87 89

5.430531 5.825515 4.322492 5.889255 5.529930 6.086642 5.000752 4.090630

91 93 94 97 98 99 101 102

5.181336 4.801076 4.676863 4.070036 5.859680 4.337256 4.882258 5.025275

104 105 108 110 111 112 114 116

4.538053 5.841144 4.106776 4.147098 4.318803 4.143023 4.670770 3.206190

117 119 120 121 122 123 127 128

4.919463 4.891486 4.402009 4.073373 4.148257 4.298796 5.121814 5.538658

129 130 132 133 134 140 141 142

3.406342 4.545065 3.567231 5.023060 4.427402 3.925790 4.425851 4.149352

143

3.081519 ## Applying the model to our testing dataset.

predict(train.mod, newdata = htest) # produces predicted values from our training model, using the testing data. 3 5 11 14 15 16 23 25

7.318721 6.910581 6.959649 6.505973 6.806142 6.787351 6.734791 5.849235

26 27 28 30 32 33 36 40

6.418403 6.462812 6.528031 6.853932 6.021541 5.226853 6.743818 6.746631

43 45 47 48 49 50 52 56

5.450941 6.852365 5.854924 6.248302 6.519124 6.066788 5.977630 6.841798

57 59 64 66 69 71 72 73

6.114564 5.720941 6.113327 5.501434 5.922356 5.791608 6.265510 5.398525

76 77 78 80 81 82 83 90

6.098167 6.296563 5.761549 5.550235 6.559611 5.559175 6.011906 4.344333

92 95 96 100 103 106 107 109

5.029329 5.246298 4.066328 5.507476 NA 5.519041 3.874870 4.060831

113 115 118 124 125 126 131 135

4.258512 4.980537 4.807166 3.986804 5.010633 4.248014 4.208966 4.878107

136 137 138 139

3.686886 5.114035 4.410461 4.028756 predval.test <- predict(train.mod, newdata = htest) # saves these predicted values from the testing dataset.

## Calculating R^2

test.mod.resid <- htest$Ladder.score - predval.test

SSE <- sum(test.mod.resid^2, na.rm = T)

SSE[1] 19.87085test.resid <- htest$Ladder.score - mean(htest$Ladder.score, na.rm = T)

SST <- sum(test.resid^2, na.rm = T)

(SST - SSE)/SST[1] 0.7104798You’ll often see a few different methods of evaluating model fit.

And there are different methods of defining the test and training datasets. And different packages and tutorials to do this.

Here’s one, called “Leave one out cross validation - LOOCV”; gif below via Wikipedia.

Loading required package: latticetrain.control <- trainControl(method = "LOOCV")

loocvmod <- train(Ladder.score ~ Social.support * Log.GDP.per.capita, data = h, method = "lm",

trControl = train.control, na.action = "na.omit")

print(loocvmod)Linear Regression

143 samples

2 predictor

No pre-processing

Resampling: Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation

Summary of sample sizes: 139, 139, 139, 139, 139, 139, ...

Resampling results:

RMSE Rsquared MAE

0.6342914 0.7098648 0.4796968

Tuning parameter 'intercept' was held constant at a value of TRUEIf your independent variables are highly related, then your multivariate regression slope estimates are not uniquely determined. weird things happen to your coefficients, and this makes it hard to interpret your effects.

IN R : check the “variance inflation factor” (VIF); a measure of how much one IV is related to all the other IVs in the model. “Tradition” is that if VIF is > 5 (or I’ve also seen VIF > 10) there’s a problem in the regression.

\(\huge VIF_j=\frac{1}{1-R_{j}^{2}}\)

Loading required package: carDatathere are higher-order terms (interactions) in this model

consider setting type = 'predictor'; see ?vif scale(Social.support)

2.847840

scale(Log.GDP.per.capita)

2.222549

scale(Social.support):scale(Log.GDP.per.capita)

1.433238 ## creating a highly correlated second IV for the sake of this example.

jitter(h$Healthy.life.expectancy, 300) [1] 0.63649887 0.68930612 0.71828952 0.66823278 0.78147940 0.64639281

[7] 0.66783200 0.65547462 0.71468602 0.72225337 0.71773673 0.64999642

[13] 0.62952106 0.64185465 0.72092831 0.69836634 0.64067483 0.60323449

[19] 0.61564585 0.70589567 0.74527554 0.54082440 0.57966955 0.74032124

[25] 0.52293196 0.54462176 0.75101008 0.55563685 0.60367356 0.74810486

[31] 0.69789473 0.54448689 0.56294229 0.69718620 0.62746987 0.69055692

[37] 0.62267421 0.70380172 0.62007029 0.68723153 0.74690172 0.49826800

[43] 0.58734907 0.50056514 0.69238462 0.52731539 0.57692015 0.64389105

[49] 0.57280871 0.69425428 0.82612563 0.77274534 0.38400182 0.57725457

[55] 0.70352020 0.61930331 0.55762718 0.57337490 0.53553203 0.65959492

[61] 0.45026458 NA 0.66845212 0.69307250 0.59281784 0.52861070

[67] 0.54621673 0.69875356 0.45710762 0.43500797 0.56482900 0.54559839

[73] 0.50964668 0.60188374 0.54674710 0.60113762 0.41675213 0.67774238

[79] 0.45482879 0.51207586 0.53754193 0.65166685 0.26579890 0.58060330

[85] 0.53234986 0.85807969 0.66611649 NA 0.25647428 0.12829974

[91] 0.51774245 0.49561179 0.47517286 0.47895859 0.35411168 0.25447142

[97] 0.21655523 0.58171885 0.35686944 0.51373138 0.48182973 0.20760587

[103] NA 0.31835400 0.46658725 0.34832926 0.52310604 0.28958395

[109] 0.33832352 0.33133514 0.42088085 0.27791840 0.16285129 0.31895572

[115] 0.62433954 0.30866350 0.37751970 0.43665557 0.41469131 0.38656597

[121] 0.32196352 0.25386893 0.35348747 0.26579842 0.62022055 0.43845057

[127] 0.49687114 0.62927456 0.48772773 0.38520825 0.37719937 0.40156511

[133] 0.33585422 0.29027768 0.12197319 0.39450247 0.18769012 0.21595348

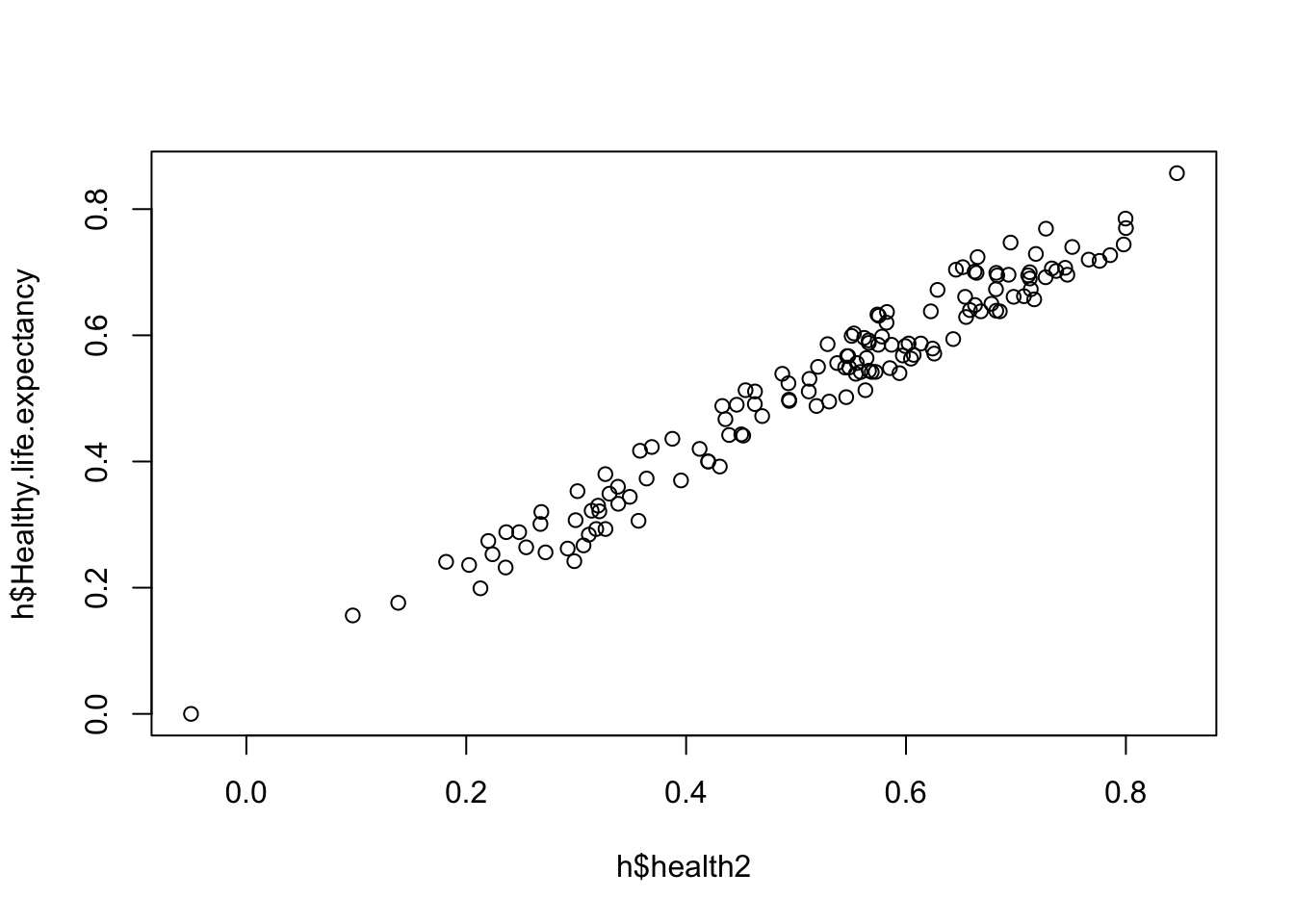

[139] 0.24276263 0.24909294 -0.03799866 0.57172747 0.27471988h$health2 <- jitter(h$Healthy.life.expectancy, 300)

plot(h$health2, h$Healthy.life.expectancy) # yup.

multimod <- lm(Ladder.score ~ Healthy.life.expectancy + health2, data = h) # both in the model.

summary(multimod) # results! Things look good....

Call:

lm(formula = Ladder.score ~ Healthy.life.expectancy + health2,

data = h)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.0155 -0.4313 0.1701 0.5191 1.5809

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.6514 0.2202 12.041 < 2e-16 ***

Healthy.life.expectancy 7.5885 1.9725 3.847 0.000182 ***

health2 -2.0676 1.8604 -1.111 0.268360

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.7703 on 137 degrees of freedom

(3 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.5809, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5747

F-statistic: 94.93 on 2 and 137 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Healthy.life.expectancy health2

24.78939 24.78939

ACTIVITY :

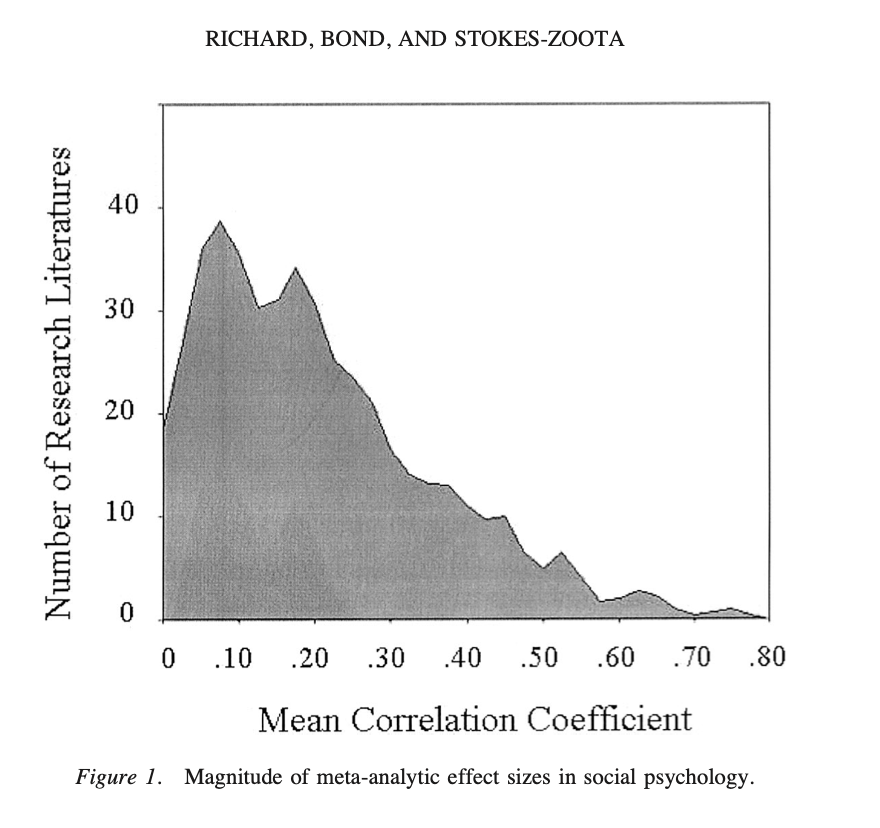

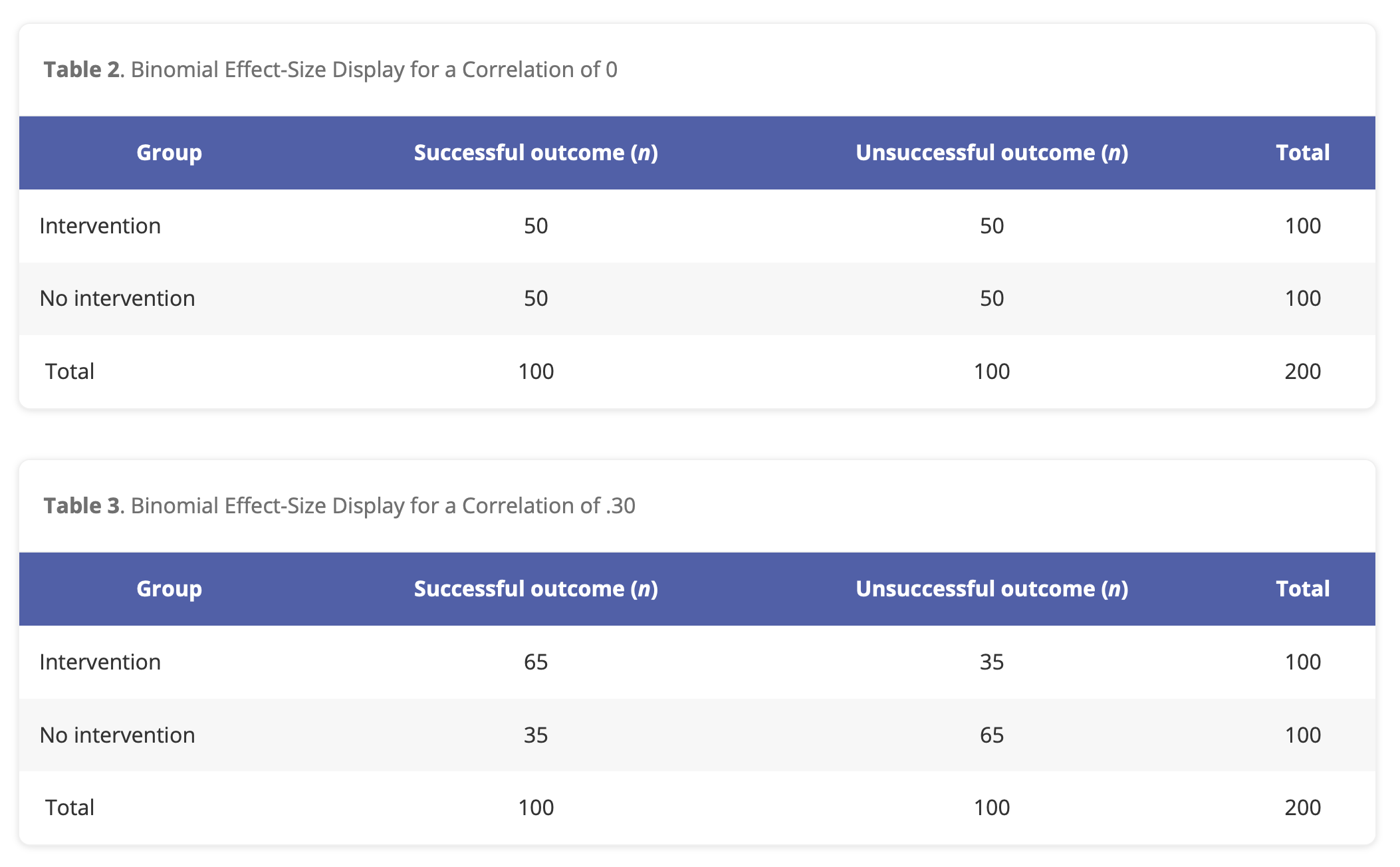

Find a “Hard Science” effect from Table 1. Does the size of this correlation surprise you? Why / why not?

Find a “Psych Science” effect from Table 2. Does the size of this correlation surprise you? Why / why not?

Farewell! Feel free to stay in touch :) it has been a pleasure and privilege to work with y’all this semester <3